Technicolor’s revolutionary three-strip process, perfected in 1932 under Herbert Kalmus, transformed cinema from black-and-white into a vivid art form that captured audiences’ imaginations. Landmark films like “The Wizard of Oz” and “Gone with the Wind” showcased the technology’s potential, while visionaries like Powell and Pressburger elevated color to new psychological depths in works such as “Black Narcissus.” This chromatic revolution permanently altered storytelling techniques, establishing color as an essential narrative tool that continues shaping cinematic language today.

The Birth and Evolution of Technicolor’s Three-Strip Process

The birth of Technicolor marked three defining decades of cinema innovation, beginning with its humble origins in 1916. From its initial two-color process experiments to the groundbreaking three-strip method, Technicolor transformed the silver screen from monochromatic memories into vibrant visions of reality.

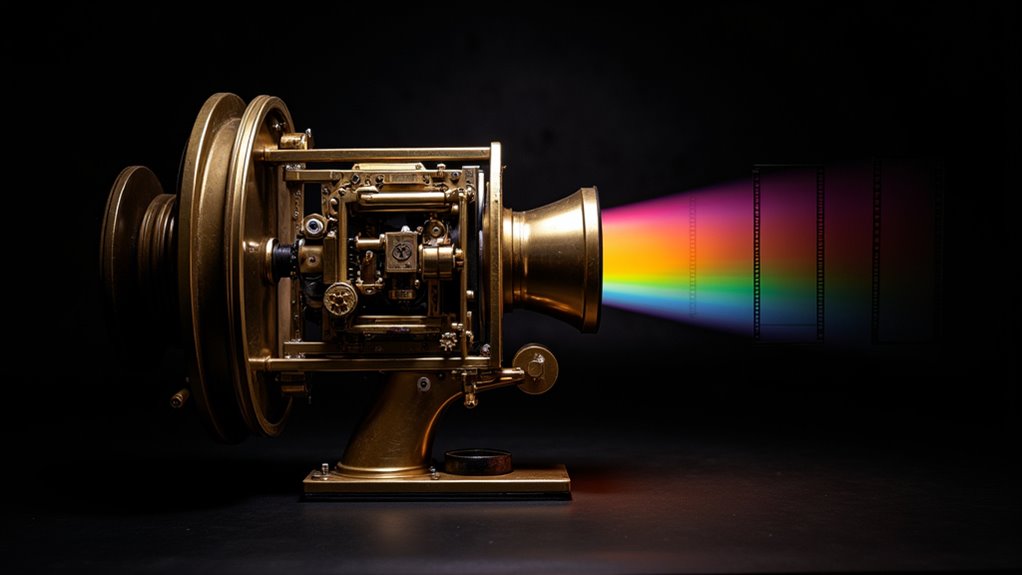

Under Herbert Kalmus’s leadership, Technicolor evolved through four distinct processes, each building upon previous technological achievements. The watershed moment came in 1932 with the completion of the three-strip camera, a beast of engineering that split light through prisms to capture red, green, and blue on separate film strips. The dye transfer process improved both the durability and vibrancy of the final prints.

This revolutionary system, known as Technicolor No. IV, dominated the industry until the 1950s, despite requiring intense illumination and precise color temperature control. While the process was notoriously expensive, keeping many productions in black-and-white, the results were nothing short of magical. The landmark film Becky Sharp (1935) demonstrated the full potential of three-strip Technicolor as the first feature to use it throughout.

Natalie Kalmus’s Color Advisory Service ensured that every frame maintained the stunning quality that became Technicolor’s hallmark.

Masterpieces That Defined the Technicolor Era

Following Technicolor’s technological revolution, a collection of cinematic masterpieces emerged that would forever alter the visual language of film.

The Wizard of Oz (1939) dazzled audiences with its transition from sepia to color, while Gone with the Wind’s sweeping landscapes proved that Technicolor could handle epic scope. The highest-grossing film of all time when adjusted for inflation demonstrated Technicolor’s mass appeal.

The iconic sepia-to-color sequence in The Wizard of Oz marked a pivotal moment when Technicolor transformed cinematic storytelling forever.

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) transformed Sherwood Forest into a vibrant playground of emerald greens and crimson reds. The film’s groundbreaking fantasy elements established a new visual standard for the genre.

The process reached artistic maturity in the hands of visionary filmmakers like Powell and Pressburger, whose Black Narcissus and The Red Shoes elevated color from mere spectacle to psychological expression. Directors utilized color to enhance themes in their visual storytelling, creating deeper emotional connections with audiences.

Meanwhile, Disney revolutionized animation with Snow White and Fantasia, using Technicolor to create otherworldly realms that still captivate viewers.

The Cultural Impact and Lasting Legacy of Color in Film

Since pioneering filmmakers first painted their worlds in vibrant hues, color has fundamentally transformed cinema’s cultural DNA, reshaping how audiences process visual storytelling and emotional resonance on screen.

The transition from black-and-white to Technicolor marked more than just a technical evolution; it revolutionized how stories were told and experienced, with films like The Wizard of Oz using color to create stark contrasts between reality and fantasy. The film’s innovative use of sepia-toned Kansas scenes juxtaposed against the vivid colors of Oz established a powerful visual metaphor for transformation that resonates to this day. Early filmmakers employed techniques like hand coloring to experiment with color before Technicolor’s invention. During the Golden Era, filmmakers mastered these color techniques to create enduring masterpieces that defined the period.

This chromatic revolution rippled through global cinema, as filmmakers discovered that different cultures interpreted colors uniquely, leading to diverse approaches in visual storytelling.

The psychological impact of color became a powerful tool, with directors carefully crafting palettes to manipulate audience emotions and enhance narrative depth.

Today, in our digital age, this legacy continues as filmmakers push creative boundaries through sophisticated color grading, proving that color remains more than mere decoration – it’s an essential language of cinema that speaks directly to our collective unconscious.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Much Did It Cost to Shoot a Film in Technicolor?

Shooting in Technicolor typically increased a film’s budget by approximately 50% compared to black-and-white productions.

Studios had to rent specialized cameras, hire additional technicians and color supervisors, and account for triple film usage.

The process required intense lighting setups that drove up electricity costs, while the dye transfer projection process added further expenses.

Major productions could see hundreds of thousands of dollars in additional costs.

What Happened to the Original Technicolor Cameras and Equipment?

Most original Technicolor cameras and equipment were discarded or deteriorated after the advent of single-strip color film in the 1950s.

The massive three-strip cameras, once Hollywood’s crown jewels, became obsolete relics gathering dust in storage facilities.

Today, only a handful of these pioneering machines survive in museums like the George Eastman Museum, serving as silent witnesses to cinema’s vibrant technological evolution.

Did Technicolor Cause Any Health Issues for Actors or Crew?

Early Technicolor production posed several documented health risks for both actors and crew members.

The intense lighting required for filming caused eye strain and headaches, while long working hours led to widespread burnout.

Crew faced additional hazards from handling chemical processing materials and operating heavy equipment.

Some actors reported skin irritation from the heavy makeup needed to appear natural under the harsh lighting conditions.

Were Any Famous Directors Strongly Opposed to Using Technicolor?

Several prominent directors expressed strong resistance to Technicolor, with Charlie Chaplin being among the most vocal opponents. He believed color would detract from the emotional power of his storytelling, sticking to black-and-white through most of his career.

Similarly, Fritz Lang viewed Technicolor as potentially distracting, while Orson Welles initially resisted it, feeling it lacked the dramatic contrast he achieved in black-and-white cinematography.

Could Technicolor Films Be Shown in All Movie Theaters?

Technicolor films could not be shown in all theaters due to significant technical and financial barriers.

Many smaller venues lacked the specialized projection equipment and lighting systems required for Technicolor screenings, while others couldn’t afford the higher rental costs.

The process demanded specific technical expertise and environmental conditions, making it primarily accessible to larger, well-funded theaters in urban areas during its early years.